As a local plumbing expert who's passionate about helping Wyoming homeowners protect their water quality and plumbing systems. From historial research to key insights from the 2004 Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) Source Water Assessment Project (SWAP) Final Report prepared by TriHydro Corporation—like delineation zones, contaminant risks, and susceptibility scoring—we hope to bring a better understanding to Cheyenne's water history and why in-home filtration is a highly recommended.

The History of Cheyenne’s Water Supply and Why In-Home Filtration Matters

As a Wyoming homeowner, your tap water tells a story of frontier resilience, engineering triumphs, and ongoing battles against natural contaminants. This article explores Cheyenne's water history—from Crow Creek's humble beginnings to modern trans-basin systems—and explains common quality issues that can wreak havoc on your plumbing.

The Early Days of Cheyenne's Water Supply

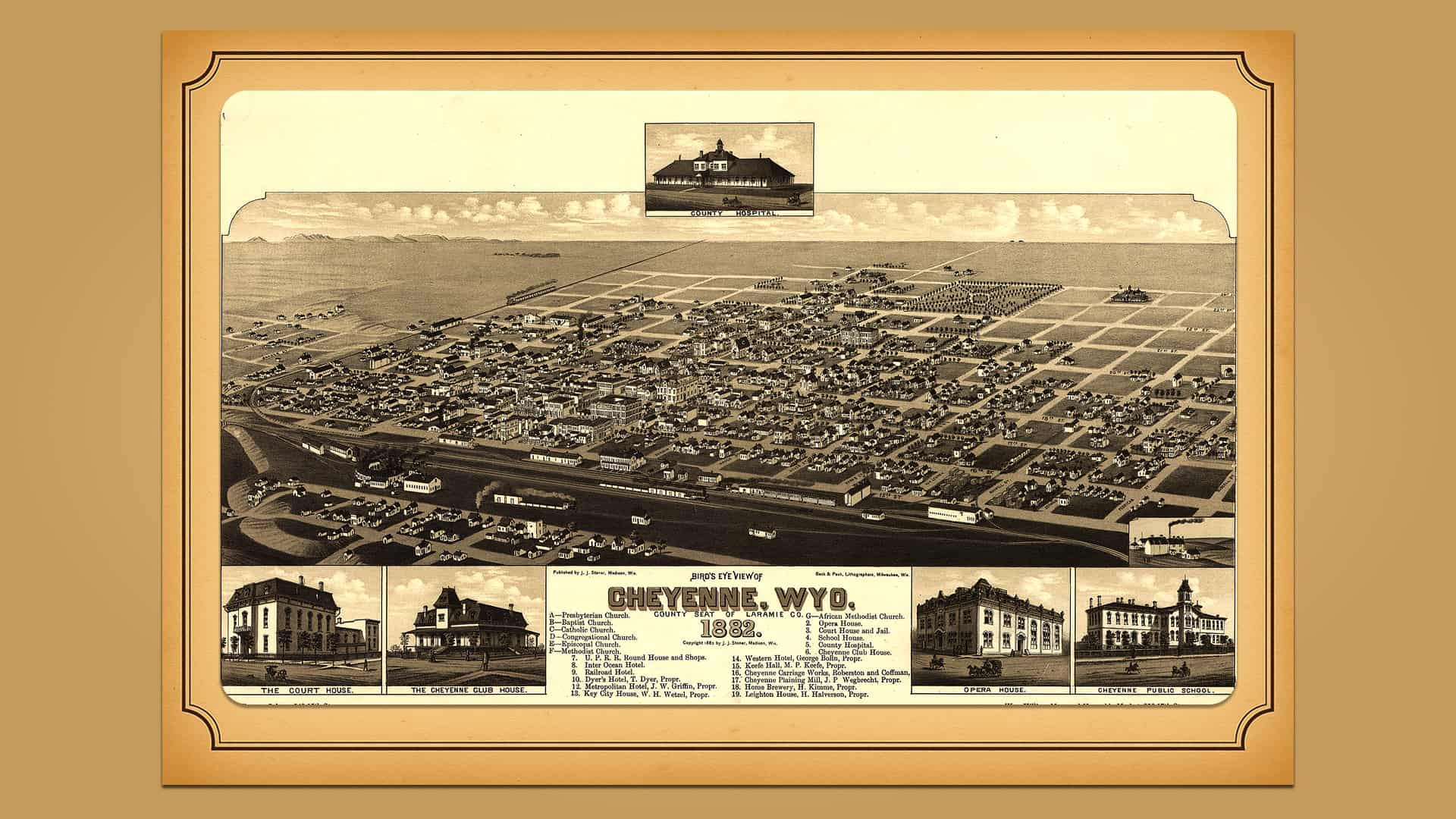

The journey of Cheyenne's water supply began with the natural flow of Crow Creek, a modest stream originating from the Rockies that served as the lifeline for early settlers and railroad workers in 1867. Initially, residents relied on direct access to the creek or shallow hand-dug wells, drawing untreated water straight from the source without any municipal infrastructure.

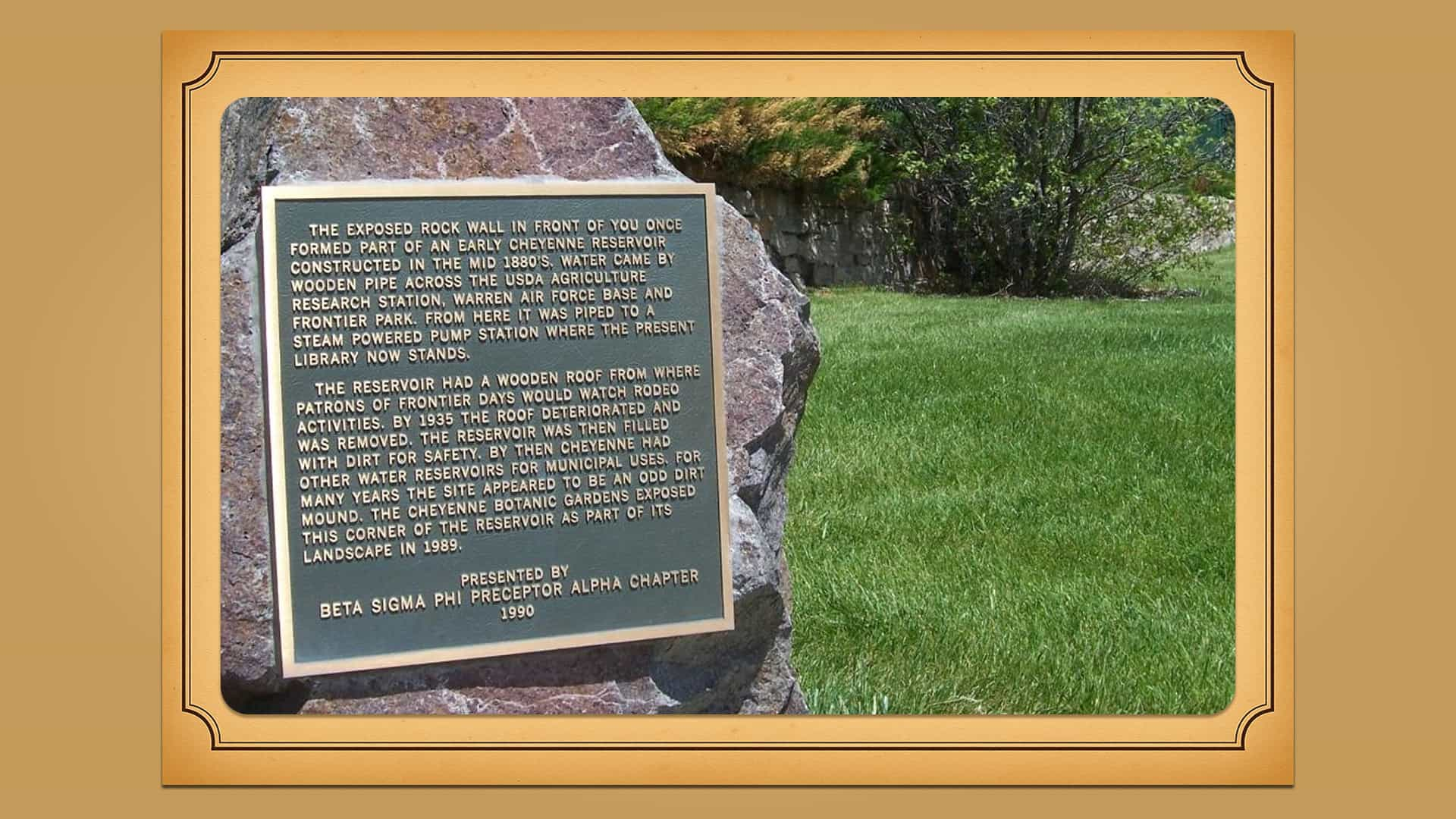

This raw supply, while essential, was vulnerable to environmental fluctuations and potential contaminants, much like the surface water systems assessed in the 2004 SWAP report, which highlights how streams can rapidly convey pollutants from upstream sources. By 1882, the transition to the city's first municipal water system marked a pivotal shift, introducing pipes that distributed water more reliably to homes and businesses. However, as noted in the SWAP data sources, such early systems often lacked comprehensive mapping of contributing areas, leaving them susceptible to unseen risks like sediment and microbial infiltration—issues that modern plumbing solutions, like backflow preventers from Aspen Mountain Plumbing, help mitigate today.

The timeline of Cheyenne's water development from 1867 to 1930 reflects a period of rapid innovation driven by necessity. In 1867, Cheyenne was established as a bustling frontier city, with water hauled manually from Crow Creek amid the semi-arid plains receiving just 15 inches of annual rainfall. By 1882, the first municipal pipes were laid, transforming daily life, followed by the 1892 completion of a new downtown pumphouse to pump and store water more efficiently.

The 1890s brought alarms about reservoir contamination, leading to the construction of Granite Reservoir in 1904 and Crystal Reservoir in 1910 for expanded storage. The Roundtop Water Filtration Plant opened in 1915, introducing basic purification, while the downtown pumphouse was decommissioned in 1920. By 1930, municipal wells began tapping deeper aquifers, as detailed in the SWAP report's use of State Engineer's Office (SEO) databases, which compiled well permit data to assess groundwater sources—insights that underscore the importance of regular plumbing inspections to prevent historical contamination patterns from affecting contemporary home systems.

Early challenges in Cheyenne's water supply were epitomized by inconsistent sources, such as the fickle nature of Crow Creek, which could overflow during wet seasons and dwindle to a trickle in dry periods. This variability not only disrupted daily access but also introduced risks of contamination from sediment, organic matter, and pollutants carried by erratic flows, as early city records noted accumulations of mud and fungus in reservoirs. Without modern treatment, residents faced foul-tasting and potentially unsafe water, mirroring the non-point source pollution concerns in the SWAP contaminant inventory, including urban runoff and agricultural impacts. These inconsistencies pushed city leaders to expand infrastructure, but they also highlight ongoing plumbing vulnerabilities, like pipe scaling from sediment buildup—problems we at Aspen Mountain Plumbing address with expert drain cleaning and filtration installations to ensure steady, clean flow in Wyoming homes.

The 2004 SWAP report, developed by the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) with TriHydro Corporation, places significant focus on surface water variability, delineating source water areas into three zones to assess risks. Zone 1, the immediate 100-foot radius around intakes, emphasizes accident prevention; Zone 2 covers attenuation areas like perennial streams extending up to 15 miles upstream; and Zone 3 encompasses entire drainage basins. For systems like Cheyenne's early reliance on Crow Creek, this framework evaluates how seasonal fluctuations can heighten susceptibility to contaminants, using GIS data and hydrologic models to map potential threats. By applying conservative hydrogeologic methods, SWAP helps communities like ours identify and mitigate variability, informing plumbing strategies such as installing whole-home filtration to buffer against these natural inconsistencies and protect residential water quality.

As surface water proved unreliable, Cheyenne turned to groundwater solutions, with early wells tapping aquifers like the High Plains Aquifer starting in the 1930s, though exploratory drilling began as early as 1930 references to SEO well databases and USGS reports). These wells, often completed in unconfined or alluvial formations, provided a buffer against droughts but required careful assessment under SWAP guidelines, which classify aquifer types (e.g., confined vs. fractured) and sensitivity scores from 1 to 10 points. Data from sources like the Wyoming State Geological Survey (WSGS) helped delineate 2-year and 5-year time-of-travel zones for contaminants, revealing how shallow wells under 65 feet could be influenced by surface water. This historical shift underscores the need for homeowners to monitor well integrity in their own systems, where Aspen Mountain Plumbing offers inspections to prevent groundwater-related issues from compromising household plumbing.

Water hardness issues emerged prominently with the tapping of these aquifers, as the High Plains groundwater introduced high levels of calcium and magnesium, leading to chalky residues on fixtures and reduced pipe efficiency—challenges that persist in Cheyenne's current blended supply. Historically, groundwater supplied about 25–30% of Cheyenne’s water. A 2020 analysis allowed this figure to be reduced to as little as 15% in wet years, though the precise blend varies depending on drought or runoff conditions. The SWAP susceptibility analysis rates such mineral content under "Other Contaminants," evaluating well integrity scores (1-13 points) and overall ratings (low to high) to gauge risks like corrosion from dissolved solids.

Historical reports of "filth" in early reservoirs align with modern detections of nitrates and trace elements, which can exacerbate scaling in water heaters and pipes. For Wyoming homeowners, this means investing in water softeners or filtration systems is crucial; at Aspen Mountain Plumbing, we specialize in custom installations that combat hardness, extending appliance life and ensuring your water remains as pristine as the Medicine Bow snowmelt.

Engineering Feats and Aquifer Reliance

Cheyenne's water story is a blend of incredible engineering feats and smart reliance on underground aquifers, all designed to bring reliable water to your tap despite our dry prairie climate. Think of engineering feats as the big projects—like building massive dams, reservoirs, and pipelines—that capture snowmelt from distant mountains and transport it across miles to the city. For instance, projects like Stage I (planning and authorization in 1963, with water first reaching Cheyenne in 1965 and final completion around 1966) and 1988 Stage II initiatives created pipelines that cross the Continental Divide, pulling water from places like Rob Roy Reservoir over 80 miles away.

Aquifer reliance, on the other hand, means tapping into natural underground water storage, such as the High Plains Aquifer, which acts like a backup reservoir during droughts. As highlighted in the 2004 SWAP report, these systems ensure a steady supply, but they also pick up minerals along the way that can affect your home's plumbing—leading to issues like scaling in pipes or reduced water heater efficiency. At Aspen Mountain Plumbing, we help homeowners navigate this by recommending simple upgrades like water softeners to keep everything flowing smoothly.

This reliance on aquifers brings us to the important idea of groundwater sensitivity, which is basically how easily underground water can get contaminated by things on the surface. In simple terms, it's like assessing how "leaky" the ground is—if pollutants from farms, roads, or spills can seep down quickly, the aquifer is more sensitive and at higher risk. The SWAP report scores this sensitivity on a scale of 1 to 10 points, factoring in things like soil type, depth to water, and slope of the land.

For example, a low score means the aquifer is well-protected and less likely to let contaminants in, while a high score (like 5 points for shallow or fractured areas, plus extra for recent chemical detections) signals greater vulnerability. For homeowners, this matters because sensitive groundwater can lead to tap water with unwanted minerals or traces of pollutants, potentially causing clogs, odd tastes, or even health concerns—making in-home filtration a smart, easy way to add an extra layer of protection without overhauling the city's system.

When it comes to aquifers, the key difference is between confined and unconfined types, and understanding this can help you protect your home's water quality. A confined aquifer is like water trapped in a sealed bottle deep underground, sandwiched between layers of impermeable rock or clay that act as natural barriers, making it harder for surface contaminants to reach (often scoring just 1 point in sensitivity per the SWAP report. An unconfined aquifer, however, is more like an open sponge near the surface, directly exposed to rainfall, spills, or runoff, which makes it more vulnerable—think shallow alluvial wells under 65 feet deep that can score up to 5 points and even be influenced by nearby streams.

For the average homeowner, this distinction matters because unconfined aquifers, common in parts of Cheyenne's High Plains system, are more prone to picking up hardness-causing minerals or pollutants like nitrates, leading to pipe corrosion or buildup in your showerheads. That's why we at Aspen Mountain Plumbing often suggest testing your water and installing targeted softeners or filters—especially if your home draws from sensitive sources—to prevent costly repairs and ensure safe, clean water for your family.

Risks in Trans-Basin Systems Like Rob Roy Reservoir

Rob Roy Reservoir has a fascinating history rooted in Wyoming's push for reliable water in the mid-20th century, starting as part of bold engineering efforts to combat droughts and support growing communities like Cheyenne. Construction began in the 1960s, with the reservoir completed in 1966 as a key component of the Stage I Project, which aimed to divert water from the Douglas Creek drainage across the Continental Divide. The reservoir, established near the historic Last Chance gold camp of 1868, is believed to have been named after a surveyor’s son.

Its precise naming story is thinner in historical record, and should be treated as such. It was built high in the Medicine Bow Mountains at over 9,000 feet elevation, with a normal storage capacity of approximately 35,000 acre-feet, using earthfill dams and spillways designed to capture pristine snowmelt. As detailed in the 2004 SWAP report, data from sources like USGS topographic maps and hydrologic unit codes helped map such reservoirs, ensuring they integrated with broader water systems. For local homeowners, this history means the water in your tap has traveled a long, engineered path—understanding it can help you appreciate why seasonal changes might affect your home's water taste or clarity.

The importance of Rob Roy Reservoir can't be overstated for Cheyenne residents—it's essentially the starting point for much of the clean, high-elevation water that makes up a significant portion of our city's supply, providing a vital buffer against dry spells in our semi-arid region. Sitting at a cooler, higher altitude, it collects purer snowmelt with fewer organic compounds compared to lower reservoirs, which then flows through pipelines to blend with groundwater before reaching your faucet. According to the SWAP report, reservoirs like this are critical in surface water delineations, forming the headwaters of Zone 3 zones that encompass entire drainage basins to protect against distant contaminants.

This means Rob Roy helps ensure a consistent flow year-round, reducing reliance on variable local sources like Crow Creek and supporting everything from daily showers to lawn irrigation—but it also underscores the need for home-level safeguards, like the filtration systems we install at Aspen Mountain Plumbing, to handle any traces that slip through municipal treatment.

While Rob Roy and similar trans-basin systems are engineering marvels, they come with inherent risks that homeowners should know about, as outlined in the SWAP susceptibility analysis.

First, seasonal variability can lead to issues like algae growth in warmer months, introducing earthy tastes or organic contaminants that affect water quality downstream.

Second, the long pipelines crossing diverse landscapes pick up minerals and potential pollutants from point sources (like NPDES discharge sites or oil/gas wells) or non-point sources (such as agricultural runoff or urban development), heightening susceptibility scores to high levels (up to 10 points for surface water systems).

Third, upstream events like forest fires or spills in the vast Zone 3 drainage basins can rapidly convey microorganisms, nitrates, or carcinogens to the reservoir, as SWAP zones evaluate time-of-travel risks. For Cheyenne families, these risks translate to potential pipe scaling, odd odors, or health concerns—that's why we recommend regular water testing and custom filtration installations to mitigate them effectively.

Understanding What Your Tap Water Carries and Why Filtration Matters

The engineering behind Cheyenne's water reservoirs is a marvel of human ingenuity, designed to capture and store snowmelt from the Medicine Bow and Laramie Mountains to supply our semi-arid region. These structures, often earthfill or concrete dams, are built at high elevations with spillways, outlets, and monitoring systems to manage water levels and prevent overflows, as mapped in the SWAP report using USGS topographic data and hydrologic unit codes.

Key reservoirs in the area include Rob Roy (completed in 1966, with a normal storage capacity of approximately 35,000 acre-feet at over 9,000 feet), Lake Owen (part of the trans-basin system for reliable flow), Granite Springs (rehabilitated in 1986 to approximately 5,200 acre-feet), and Crystal Lake (built in 1910 for lower-elevation storage). Each plays a unique role—higher ones like Rob Roy provide clearer, colder water, while lower ones like Granite Springs are more prone to warming and organic buildup.

For homeowners, this means your tap water's journey starts with these engineered giants, but it can carry sediments or minerals that lead to plumbing woes, making regular checks and filtration key to avoiding costly repairs.

On a mass scale, Cheyenne's water treatment plants, like the R.L. Sherard facility on Happy Jack Road (built in 1975 and modernized in 2002 with a firm capacity of 32 million gallons per day), use a multi-step process to purify raw water from reservoirs and aquifers before it reaches your home. The process involves coagulation to clump particles, filtration through sand and gravel beds, disinfection with chlorine to kill pathogens, blending with groundwater, and pH adjustments to prevent pipe corrosion—all informed by SWAP's susceptibility scoring for intakes.

That distinctive bad smell you might notice near these plants often comes from the chlorine disinfection step, which creates a chemical odor similar to a swimming pool, or from organic matter breaking down during treatment, releasing sulfur-like gases. It's a necessary evil to ensure safety, but for homeowners, it highlights that while plants handle major threats like bacteria (rated as "Serious Contaminants" in SWAP), they don't always eliminate every trace mineral or taste—that's where in-home filtration from Aspen Mountain Plumbing steps in to refine what's left.

Findings from USGS data, as integrated into the SWAP report's delineation and sensitivity mapping, reveal shocking levels of mineral pickup in Cheyenne's water sources that can stun any homeowner. For instance, water traveling through trans-basin pipelines and reservoirs absorbs calcium, magnesium, iron, and silica from ancient rock formations, with USGS hydrogeologic reports showing dissolved solids often exceeding 500 parts per million—far higher than in softer water regions, leading to "very hard" classifications that can shorten water heater lifespans by up to 50% due to scaling.

Even more alarming, trace elements like arsenic or radionuclides from natural geologic sources have been detected at levels nearing EPA limits in some Wyoming basins, potentially infiltrating unconfined aquifers with sensitivity scores up to 10 points. Imagine discovering that the snowmelt feeding your faucet carries enough minerals to coat your pipes like a hidden rust bomb—it's a wake-up call that municipal treatment alone can't fully neutralize, urging homeowners to install softeners or filters to protect their systems and health.

Believe it or not, a true story from Wyoming's industrial past illustrates the hidden dangers of carcinogens in our water sources, as documented in SWAP's contaminant inventory (Superfund and groundwater pollution sites). In the late 1990s, a former refinery site in a Wyoming community—part of the three Superfund (CERCLA) locations identified by EPA data in the report—leaked hydrocarbons and known carcinogens like benzene into the groundwater, contaminating nearby public wells despite being miles away. Homeowners reported odd odors and health issues, only to learn through DEQ investigations that these "Serious Contaminants" had migrated via fractured aquifers (rated high susceptibility in SWAP matrices), affecting drinking water for years before remediation under the Voluntary Remediation Program (VRP).

One family, thinking their tap water was safe, discovered elevated cancer risks from trace exposures—a shocking reality that led to community-wide filtration mandates. At Aspen Mountain Plumbing, we've seen similar scares; it's why we advocate for home testing and advanced filters to guard against such invisible threats lurking in industrial legacies.

Common Water Quality Issues in Cheyenne

Testing for Public Water Systems (PWS) like Cheyenne's involves a rigorous process to ensure accuracy and safety, as outlined in the SWAP report's quality assurance and quality control measures, which include verifying data from multiple sources like sanitary surveys, GIS mapping, and operator feedback to create reliable assessments. This builds trust by confirming that every detail—from well locations to contaminant risks—is double-checked, often incorporating input from local experts and the Wyoming Association of Rural Water Systems (WARWS). For example, the report highlights how irrigated agriculture, a common land use in Wyoming's basins, contributes nitrates as a non-point source pollutant, with percentages evaluated across delineation zones—in areas where over 40% of Zone 2 or 3 land is irrigated, it triggers a high contaminant rating.

In Cheyenne's blended system, this means routine testing detects elevated nitrates from nearby farming runoff, reassuring homeowners that DEQ's voluntary assessments (using tools like the SEO well database) catch these issues early, preventing them from escalating into household problems like discolored water or pipe damage.

Preventing these risks through in-home filtration is a straightforward step every Cheyenne homeowner can take, turning potential water quality headaches into worry-free reliability. Filtration systems, such as reverse osmosis units or whole-home softeners, act as a final barrier against common issues like nitrates from agricultural sources or minerals causing hardness, filtering them out before they reach your faucets and appliances. For instance, if testing reveals high susceptibility in your local PWS (as per SWAP's 1-10 sensitivity scores), a targeted under-sink filter can remove up to 99% of contaminants, extending the life of your water heater and reducing scaling in pipes—saving you hundreds in repairs over time. At Aspen Mountain Plumbing, we educate families on affordable options tailored to Wyoming's geology, like installing systems that handle seasonal algae from reservoirs, ensuring your water stays clean, tasty, and safe without relying solely on municipal treatment.

The SWAP report places strong emphasis on evaluating susceptibility to "Serious Contaminants," which are the most threatening pollutants like microorganisms, nitrates/nitrites, and carcinogens that pose significant health risks if they infiltrate water supplies. This evaluation uses detailed matrices to rate risks across zones—for example, any serious contaminant in Zones 1 or 2 automatically gets a high rating, while known releases in Zone 3 bump it to medium, combining with well integrity scores (1-13 points) to assign overall low, medium, or high susceptibility.

Understanding that vulnerabilities in our trans-basin and aquifer systems could allow carcinogens from industrial sites or nitrates from agriculture to affect tap water, potentially leading to long-term health concerns or plumbing corrosion. Prioritize these things. Cheyenne's water history—from Crow Creek to Rob Roy—is a testament to Wyoming ingenuity, but SWAP insights remind us that risks like hardness, nitrates, and carcinogens persist, impacting your plumbing and health.

It's time to take proactive steps like installing filtration to ensure pure, reliable water. Contact Aspen Mountain Plumbing for a free water quality assessment and custom solutions—keep your home's water flowing soft and clean!

Written by Travis James, franchise owner of Aspen Mountain Plumbing in Cheyenne, Wyoming.